For more than 40 years, the Golden State Killer had been on the loose. Police had linked the notorious serial killer to a dozen murders and more than 50 rapes across California from 1976 to ’86, yet he’d eluded all their attempts to find him. The case had seemingly gone cold.

But investigators say they’ve finally cracked it. Last spring, they arrested a man in a Sacramento suburb who they think committed these heinous crimes. As the suspect, a 72-year-old retired police officer named Joseph James DeAngelo, awaits trial, many people across California are breathing a sigh of relief.

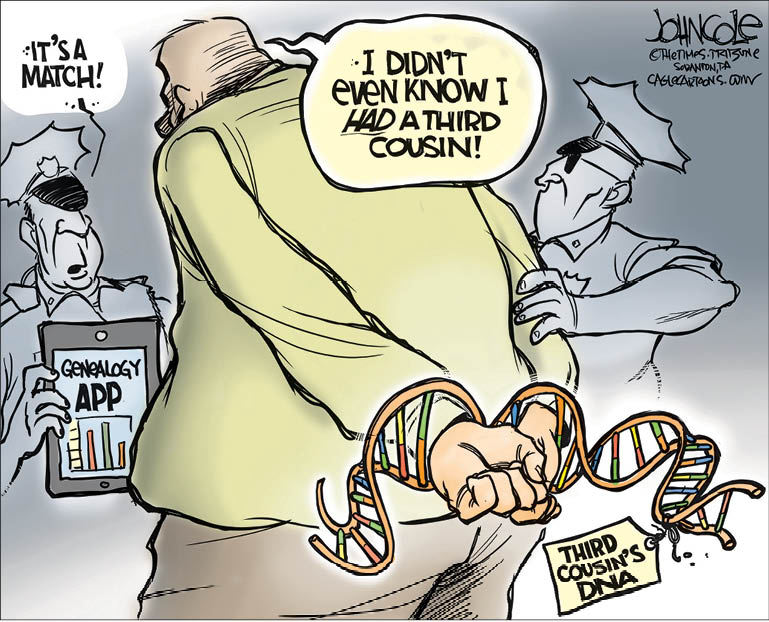

The way the police found DeAngelo, however, has many civil liberties experts concerned. That’s because police tracked him down using a public genealogy database called GEDmatch.

Genealogy services have become increasingly popular in recent years. More than 15 million people in the U.S. have offered up their DNA—a cheek swab or some saliva in a test tube—to services such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe in pursuit of answers about their heritage or to gauge their risk for certain medical conditions. In exchange for a genetic fingerprint, individuals may find a birth parent, long-lost cousins, perhaps even a link to George Washington or Queen Victoria.

For more than 40 years, the Golden State Killer had been on the loose. Police had linked the notorious serial killer to a dozen murders and more than 50 rapes across California from 1976 to ’86. Yet he’d eluded all their attempts to find him. The case had seemingly gone cold.

But investigators say they’ve finally cracked it. Last spring, they arrested a man in a Sacramento suburb who they think committed these terrible crimes. The suspect is a 72-year-old retired police officer named Joseph James DeAngelo. As he awaits trial, many people across California are breathing a sigh of relief.

But the way the police found DeAngelo has many civil liberties experts concerned. That’s because police tracked him down using a public genealogy database called GEDmatch.

Genealogy services have become very popular in recent years. More than 15 million people in the U.S. have offered up their DNA to services such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe. It’s been as simple as a cheek swab or some saliva in a test tube. Some people have used these services to find answers about their heritage. Others want to check their risk for certain medical conditions. In exchange for a genetic fingerprint, individuals may find a birth parent or long-lost cousins. They might even find a link to George Washington or Queen Victoria.