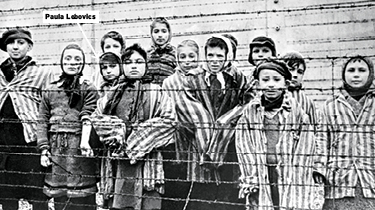

Paula Lebovics was 11 years old, starving, cold, and reduced to a near skeleton when soldiers from the Soviet Union entered the Auschwitz concentration camp and were stunned by the horrors they saw—the piles of naked corpses, the emaciated, bedraggled survivors barely able to walk, the rubble of what looked like a death factory. One soldier picked Lebovics up and held her in his arms.

“He was sitting down and rocking me in his arms and tears were flowing down his face, and I can never forget that as long as I live,” Lebovics said in an interview many decades later. “It was the first time I had this kind of feeling . . . somebody caring about me.”

Lebovics was one of the 7,000 frail or dying inmates the Soviet army discovered on January 27, 1945, when they liberated Auschwitz in Poland, the largest and most notorious of the concentration camps and killing centers set up by the Germans during World War II to extract slave labor for the military effort and to exterminate the Jews of Europe. More than 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. Of those, 1.1 million were murdered—1 million of them Jews, including 200,000 Jewish children.

This January will mark the 75th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation. American and British soldiers, allies of the Soviets in their battle against the Germans, also liberated concentration camps, infamous places like Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. But Auschwitz’s liberation holds a singular place in history because as the largest and most lethal of the death camps, it has become a near synonym for the wider Holocaust, in which 6 million Jewish people were murdered.

“Auschwitz has become an international symbol of evil,” says Holocaust historian Michael Berenbaum.

When soldiers from the Soviet Union entered the Auschwitz concentration camp, they found Paula Lebovics. She was 11 years old, starving, cold, and reduced to a near skeleton. The soldiers were stunned by the horrors they saw. There were piles of naked corpses and bony, unkempt survivors who were barely able to walk. There was also the rubble of what looked like a death factory. One soldier picked Lebovics up and held her in his arms.

“He was sitting down and rocking me in his arms and tears were flowing down his face, and I can never forget that as long as I live,” Lebovics said in an interview many decades later. “It was the first time I had this kind of feeling . . . somebody caring about me.”

Lebovics was one of the 7,000 frail or dying inmates the Soviet army discovered on January 27, 1945. That day, the soldiers liberated Auschwitz in Poland. It was the largest and most notorious of the concentration camps and killing centers. The Germans set up these facilities during World War II. They used them to provide slave labor for their military effort and to wipe out the Jews of Europe. More than 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. Of those, 1.1 million were murdered. One million of them were Jews, including 200,000 Jewish children.

This January marks the 75th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation. American and British soldiers were allies of the Soviets in their battle against the Germans. They also liberated concentration camps, including infamous places like Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen. But Auschwitz’s liberation holds a special place in history. That’s because it was the largest and most lethal of the death camps. And it’s become a near synonym for the wider Holocaust, in which 6 million Jewish people were murdered.

“Auschwitz has become an international symbol of evil,” says Holocaust historian Michael Berenbaum.