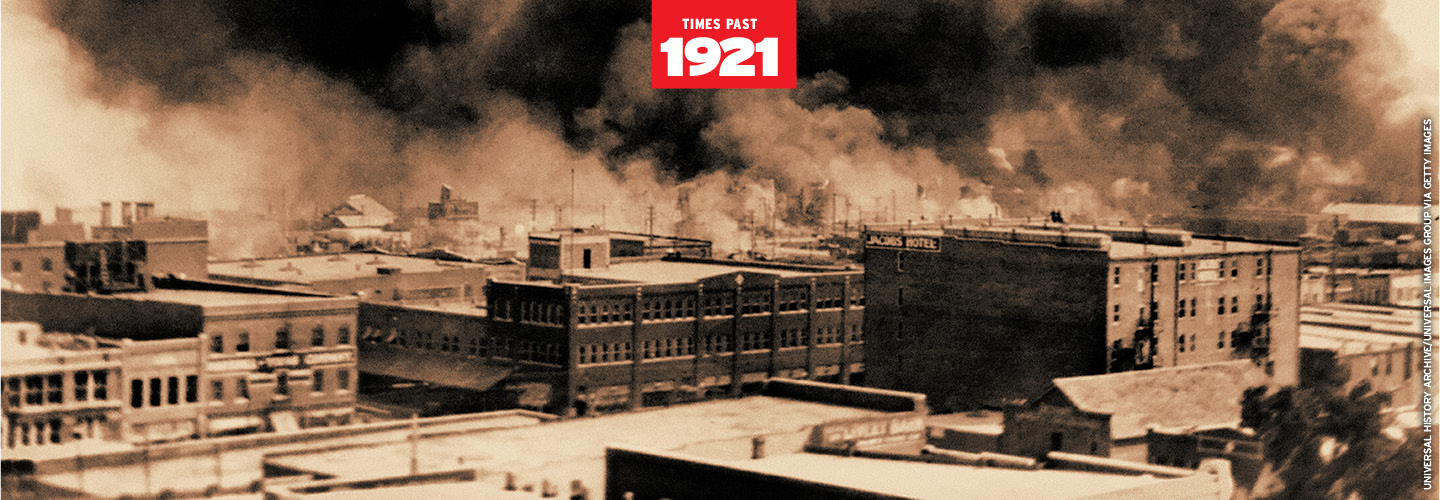

On May 30, 1921, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a thriving Black community—a rarity in an era of segregation, lynchings, and a rapidly growing Ku Klux Klan.

By sunrise on June 2, however, Greenwood lay in ruins, burned to the ground by a mob of white people, aided and abetted by the Oklahoma National Guard. The death toll may have been as high as 300, with hundreds more injured and an estimated 8,000 or more left homeless.

The Tulsa race massacre, as it came to be known, was one of the worst acts of racial violence in American history. But city officials immediately set about erasing the atrocity from the historical record. When the carnage was over, the victims were buried hastily in unmarked graves without death certificates. Police records vanished, and archival copies of some newspaper coverage of the killings were selectively expunged.

Schools didn’t teach the massacre. And generations of people—even the descendants of some of the survivors—grew up not knowing anything about it.

Now, a century after the massacre, the city of Tulsa is digging up its painful past—literally—in an effort to bring some reconciliation to the community.

On May 30, 1921, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a thriving Black community. It stood out as a rarity in an era of segregation, lynchings, and a rapidly growing Ku Klux Klan.

But by sunrise on June 2, Greenwood lay in ruins. A mob of white people burned the district to the ground. And they had gotten help from the Oklahoma National Guard to carry out their attacks. The death toll may have been as high as 300, with hundreds more injured and an estimated 8,000 or more left homeless.

It became known as the Tulsa race massacre. It was one of the worst acts of racial violence in American history. But city officials immediately set about erasing the atrocity from the historical record. When the bloodshed was over, the victims were buried quickly in unmarked graves without death certificates. Police records vanished. And even the archival copies of some newspaper coverage of the killings were deleted.

Schools didn’t teach the massacre. And generations of people grew up not knowing anything about it. Even the descendants of some of the survivors weren’t informed.

Now, a century after the massacre, the city of Tulsa is literally digging up its painful past. It’s part of an effort to help the community heal.