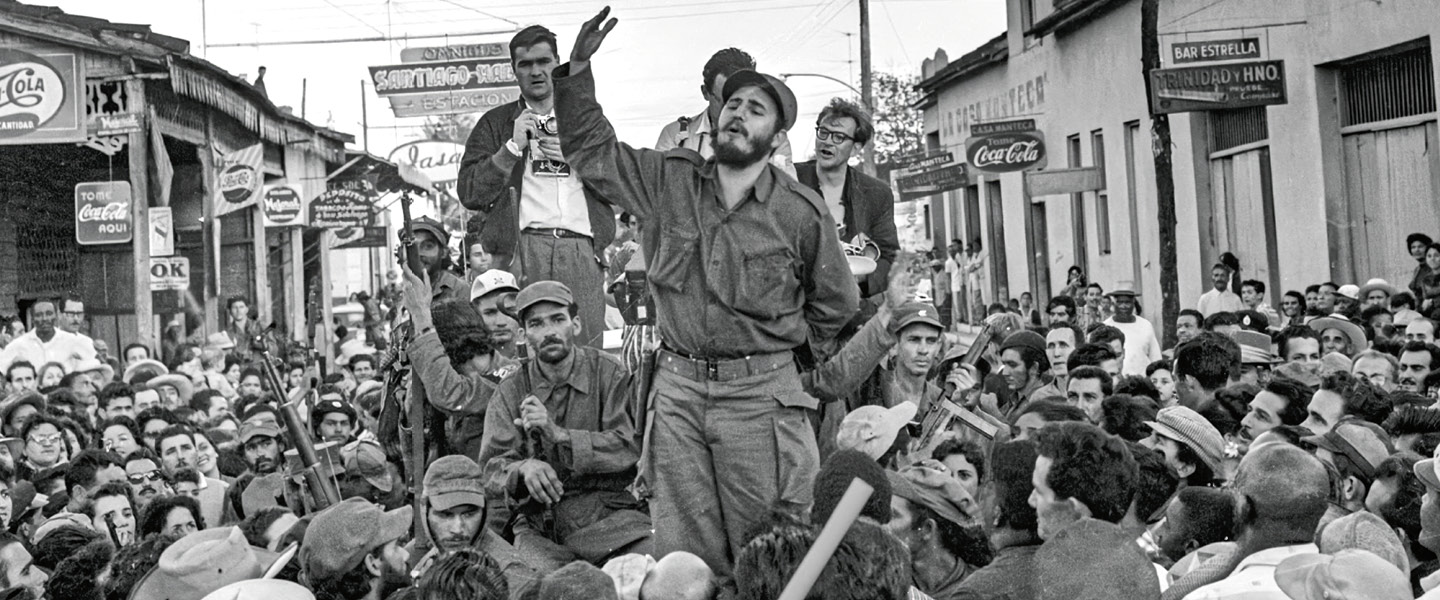

When Fidel Castro rolled into Havana, Cuba, in January of 1959 along with some 5,000 members of his triumphant rebel army, the entire city, it seemed, turned out to celebrate. Thousands poured into the streets, peered down from balconies, or perched on rooftops, many holding Cuban flags, as they showered Castro with confetti. After parading with his forces, Castro delivered a passionate speech that lasted until dawn.

“I am not interested in power,” Castro said as he claimed victory in the Cuban Revolution, “nor do I envisage assuming it at any time.”

Castro, 32, had spent two years battling the brutal, U.S.-backed dictatorship of President Fulgencio Batista. By New Year’s Eve 1958, with Castro’s guerrilla forces closing in, Batista had fled Cuba in the dark of night, marking the end of his rule.

At the time, Castro was widely hailed as a champion of the working class for liberating Cuba from an oppressive regime. But before long, everything changed. Castro’s embrace of Communism alienated Cuba from the U.S., and his promise to bring democracy and prosperity to ordinary Cubans never materialized.

Today Castro is often credited with improving Cuba’s education and health care systems, yet his repressive regime left a nation where free speech still isn’t tolerated and Cubans struggle to provide for their families.

“The situation gets worse every day,” says René de Jesús Gómez, a longtime Cuban dissident who was born in Havana. “Here, whoever doesn’t leave, it’s because they can’t.”

In January of 1959, Fidel Castro entered Havana, Cuba. He had some 5,000 members of his triumphant rebel army with him. It seemed like the entire city was celebrating. Thousands of people poured into the streets, looked down from balconies, or sat on rooftops. Many were holding Cuban flags. They showered Castro with confetti. After parading with his forces, Castro delivered a passionate speech that lasted until dawn.

“I am not interested in power,” Castro said as he claimed victory in the Cuban Revolution, “nor do I envisage assuming it at any time.”

Castro, 32, had spent two years battling the brutal, U.S.-backed dictatorship of President Fulgencio Batista. By New Year’s Eve 1958, with Castro’s forces closing in, Batista had left Cuba in the middle of the night. It marked the end of his rule.

At the time, Castro was seen as a champion of the working class because he freed Cuba from an oppressive regime. But before long, everything changed. Castro’s embrace of Communism alienated Cuba from the U.S. His promise to bring democracy and prosperity to ordinary Cubans never materialized.

Today Castro is often credited with improving Cuba’s education and health care system. But it is still a nation where free speech isn’t tolerated and Cubans struggle to provide for their families.

“The situation gets worse every day,” says René de Jesús Gómez, a longtime Cuban dissident who was born in Havana. “Here, whoever doesn’t leave, it’s because they can’t.”