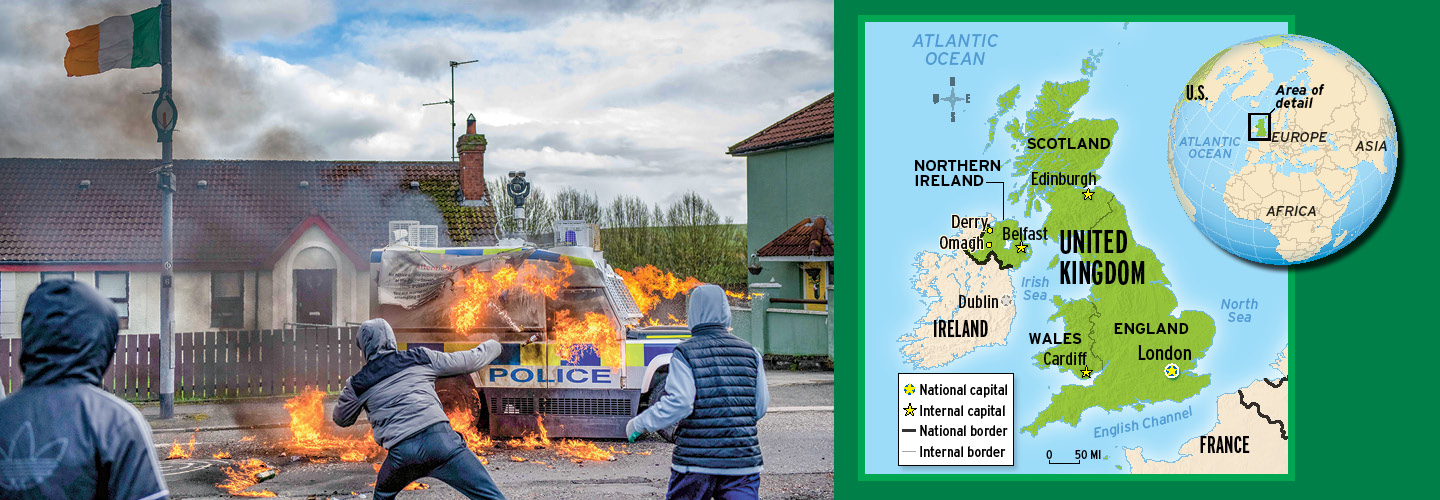

Pauline Harte was 19 years old when she lost a leg to a massive car bomb that exploded in Omagh, Northern Ireland, in 1998. The bombing, which killed 29 people, was the last and single-deadliest attack in the decades-long sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

Harte, now 43, who endured years of skin grafts to treat severe burns on her lower body, has four children and works as an art teacher. Like many in Northern Ireland, she had hoped that the violent conflict that ended a quarter century ago would remain in the past. So she was deeply shaken last February when gunmen associated with a Catholic militant group shot a police detective, one of many signs of renewed tensions that some fear could reignite the conflict.

“I lost my leg because of that violence,” says Harte. “I don’t want my children to grow up in that kind of world.”

Pauline Harte was 19 years old when she lost a leg to a massive car bomb that exploded in Omagh, Northern Ireland, in 1998. The bombing killed 29 people. It was the last and single-deadliest attack in the decades-long sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

Harte endured years of skin grafts to treat severe burns on her lower body. Now 43, she has four children and works as an art teacher. Like many in Northern Ireland, she had hoped that the violent conflict that ended a quarter century ago would remain in the past. So she was deeply shaken last February when gunmen associated with a Catholic militant group shot a police detective. It was one of many signs of renewed tensions that some fear could reignite the conflict.

“I lost my leg because of that violence,” says Harte. “I don’t want my children to grow up in that kind of world.”